In classes, we often learn that Spanish is a phonetic language.

And it’s mostly true!

Especially compared to English, written Spanish is very close to spoken Spanish.

You can look at a word you’ve never seen and know with confidence how it’s pronounced.

But technically, it’s not 100% phonetic.

Several common sounds can be represented by more than one letter.

This generates misspellings that can ruin a resumé, but can be insightful to us as learners.

In today’s Saturday Spanish, we’ll examine some common areas of spelling confusion among native speakers — and we’ll consider what we can learn from it.

Spanish misspellings fall into a few categories

Back when I was an exchange student in Chile, my spelling skills surprised my classmates.

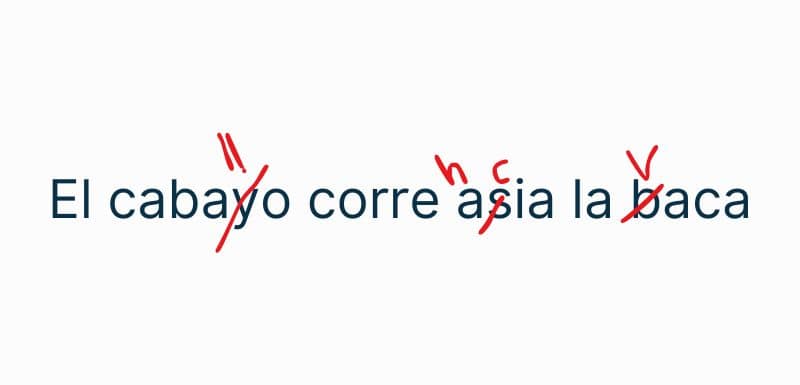

They were impressed that I knew that it’s haber and not haver, caballo and not cabayo.

Since these letters represent the same sounds, spelling errors like these are common among native speaker kids.

But since lots of my vocabulary had come from textbooks, I was familiar with the spelling from the start.

On the other hand, my Chilean classmates’ vocabulary started like anyone’s language skills: by listening to and repeating the people around them.

There’s an important lesson we can learn from these misspellings.

But first, let’s take a look at a few letters that you may see mixed up:

B/V

For most Spanish speakers, there’s no difference between B and V. Depending on the position in a word, they can soften a bit. But in most places, one letter sounds the same as the other.

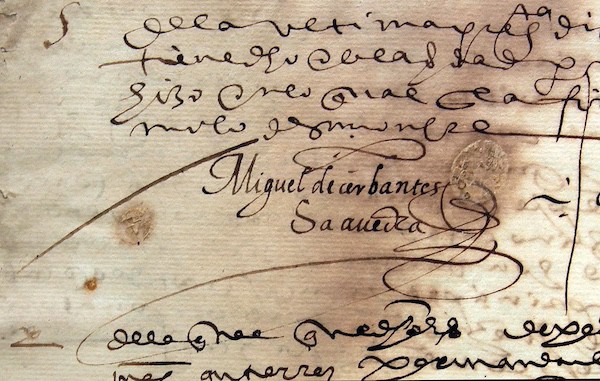

Even Cervantes signed his name Miguel de Cerbantes.

This means Spanish speakers may mistakenly swap B and V when spelling words like…

Tuvo / tubo (had / tube)

- La medicina tuvo un efecto inmediato

- El tubo está roto.

Votar / botar (vote / throw out)

- Votar es un derecho

- Botar la basura es importante.

Vaca / baca (cow / roof rack)

- La vaca da leche.

- El auto tiene una baca.

LL/Y

These two sounds don’t sound the same in Madrid as in Montevideo.

But within a city or region, LL and Y tend to represent the same sound.

Naturally, this can leave people uncertain whether to use Y or LL in situations like these…

Pollo / poyo (chicken / stone bench)

- Venden pollo asado.

- El poyo es de piedra.

Calló / cayó (silenced / fell)

- Se cayó de la silla.

- Se calló cuando comenzó la clase.

Halla / haya (find / there is)

- Halla una solución.

- Espero que haya solución

H / no H

The H is silent, which means it’s easy to leave out when it should be there, or add in when it shouldn’t be there:

Hacia / Asia (towards / Asia)

- Estamos en camino hacia la oficina

- La oficina central se encuentra en Asia

Haber / a ver (there is / let’s see)

- Va a haber mucha gente en la fiesta

- A ver cuántas personas hay en la fiesta

Hecha / echa (done / throw)

- La obra está hecha

- El niño echa basura por la ventana del bus

C/Z/S

In most of Spain, speakers differentiate between C/Z and S.

But in the rest of the Spanish speaking world (all of Latin America and parts of Spain) these three sounds sound identical, giving rise to mix ups with words like…

Cazar / casar (hunt / marry)

- El trabajo del gato es cazar ratones

- El sacerdote los va a casar

Cerrar / serrar (close / saw)

- Voy a cerrar la puerta

- Tengo que serrar una tabla de madera

Cien / sien (one hundred / temple)

- Cuesta cien pesos.

- Me duele la sien

Avoiding interference

As adult Spanish learners, it’s common to see words written before we hear them spoken (or at least at the same time).

This helps with spelling. But it has the disadvantage that we might continue associating the sound we see with how it’s pronounced in our native language.

By contrast, native speakers (of any language) hear a huge portion of their vocabulary before they ever see it written. When spelling, they start by sounding it out.

If a Colombian or Guatemalan hears cazar or tuvo and writes casar or tubo, it tells us that those sounds are the same to their ears.

It also tells us that when we speak, those sounds should sound the same… despite what the letters call for in English.

(If you’re learning Spanish from Spain, this applies to all but the C/Z/S sounds).

So if we record ourselves and notice that our “a ver” sounds different from our “haber”, it’s a signal to revisit our pronunciation of those sounds.

Learn to misspell?

Poor spelling is, of course, not the goal.

But if you are misspelling words with these letters, it might actually be a good sign – a sign that you’re thinking like a Spanish speaker in terms of sounds.

Because if you always think of H, V, C, Z, Y, etc., from an English-speaking perspective, spelling will be easy… but you’ll find it hard to shake your English pronunciation patterns.

– Connor

Looking for something more? Here’s one way I can help you:

The Confident Spanish Pronunciation Course. Join 100+ students learning to unlock better conversation skills by building clear, natural-sounding Spanish. Click here to read what current students are saying